Exhibit

Since its invention, photography has served as a window into who we are as a people, but of all its myriad inventions the panoramic camera and its images have provided the most transparent look into our society at a time when America was comprised of joiners with unbridled optimism. Panoramic photography recorded everything from military units to bands, parades, circuses and the numerous fraternal groups that formed at the turn of the century. Panoramic photographers left behind stunning images often called “yard longs” because of their unusual length sometimes reaching six feet long or more.

The Historical Society of Greater Lansing and the Library of Michigan are showcasing more than 50 panoramic photographs taken in Michigan from 1863 to 2004. The exhibit called “By the Yard: Panoramic Photography in Michigan” opens Saturday, February 11, 2023, and runs through May 1, 2023. A lecture on the history of panoramic photography will be held Saturday, February 11 at 1 p.m. at the Library of Michigan, 702 W. Kalamazoo St., Lansing MI. The lecture and parking are free and open to the public.

“By The Yard” during installation, January 2023

Most of the panoramic photographs in the exhibit represent the people, places and things of Michigan and were collected by the late Dan Barber of Lansing whose estate is donating his collection to the Library of Michigan for preservation. The collection was supplemented by loans of photographs from Libraries, Archives and private collectors from Michigan.

The exhibit showcases some of the more common visuals for panoramas such as soldiers and sailors shipping out for WWI. The soldiers and sailors would stand at parade attention as a panorama photographer would snap a shot using such long exposures that a person at one end could run to the other and appear twice in the same photograph. The photographers would then sell photos to sailors and soldiers and their families.

Panoramic photography was at its height from about 1900 to 1950 and the invention of panoramic photography can be traced to European artists who in the early part of the 19th century painted massive murals called dioramas depicting street scenes, battle scenes and travel destinations. Paying customers clamored to see these extravaganzas.

Artists and photographers have always strived to recreate what the human eye sees normally. If you look straight ahead at a single point your field of vision is about 130 degrees and a panorama image easily replicates what the human eye can see and can even go beyond that to a full 360 degrees.

The first panoramic photographs were taken by daguerreotype. Frenchman Louis Daguerre, in the 1820s, invented one of the first cameras and photo processes. His method was used to photograph a scene by taking two or more images using separate plates of a subject side by side in succession creating the first panoramic photographs. And until the invention of the swing lens Al Vista camera in 1897 that was the only method of creating panoramic photos.

The Al Vista and other similar cameras had a lens that rotated from left to right capturing an image on film which ran right to left. To create the movement a key was used to wind springs in the camera. The early images were typically 8-12 inches long and 2-three inches high. In 1904, a Canadian invented the Cirkut Camera and in the U.S. the patent was ultimately assigned to Eastman Kodak which began producing these sophisticated cameras that could, in theory, take panoramic photographs that were of infinite length. The sizes of the panoramic photographs in this exhibit show the range from a more than 50-inch long modern panorama of the 2004 Michigan House of Representatives to a hulking 80-inch photo taken at Ft. Custer in Battle Creek. Three of the photographs in the exhibit, one showing an 1863 view of the Marquette Harbor, were hand-colored by artists.

The Cirkut Camera worked differently than the swinging lense camera and was mounted on a tripod that would rotate at various speeds controlled by gears wound with a key. The camera would have a canister of film that would simultaneously feed film in the opposite direction of the rotating tripod to expose the image.

Panoramic cameras weighed up to 50 pounds and the process of setting the various controls was complex made even more complex with the necessity to herd and line up the subjects who could easily number in the hundreds or thousands as is the case with military units. Photographers soon learned that subjects also would need to line up in a concave circle so that the final product looked like they were standing in a straight line and to trick the eye of the viewer. Street scenes taken by panorama cameras often look like slices of a cake jutting at various angles from the photograph. The subjects would have to stay absolutely still or they would be blurred in the final image which can be seen in the Kalamazoo panorama showing troops returning from WWI.

Panoramic photographers often used tall tripods with some reaching to 10 feet or built towers to stand on or climbed telephone poles, water towers or to the top of tall buildings. One photograph in the exhibit shot at Ft. Custer was taken from a camera attached to a series of kites which were raised to 500 ft.

“By The Yard” during installation, January 2023

Commercial photographers embraced this new technology and rushed to the opportunities to make money and serve their customers’ needs. The cameras were expensive to buy, costing more than $400, and complex to use. Photographers would often sell small panoramic photos for as little as 25 cents.

Photographs were shot of disasters such as the Upper Peninsula train wreck in Ishpeming (shown in the exhibit) and panoramic photographs of battlefield scenes and parades began appearing in newspapers. Large gatherings of people and groups were often the focus as illustrated by several of the photographs in the exhibit. A panoramic photograph of the Ku Klux Klan assembled in Jackson, MI is part of the exhibit.

With the advent of smaller digital cameras in the 1980s panoramic photography became accessible to amateurs and today’s cell phones easily create similar images.

Many panoramic images ended up in attics in tight little rolls and were often left unframed due to the cost of framing.

Numerous images in the exhibit are from scans of originals which were too rare to display or even frame. Numerous museums, archives and collectors loaned images for the exhibit.

A cell phone panorama of “By The Yard” during installation, January 2023

Media

Lansing Decoration Day Parade, 1912; Photo by F.N. Bovee; Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

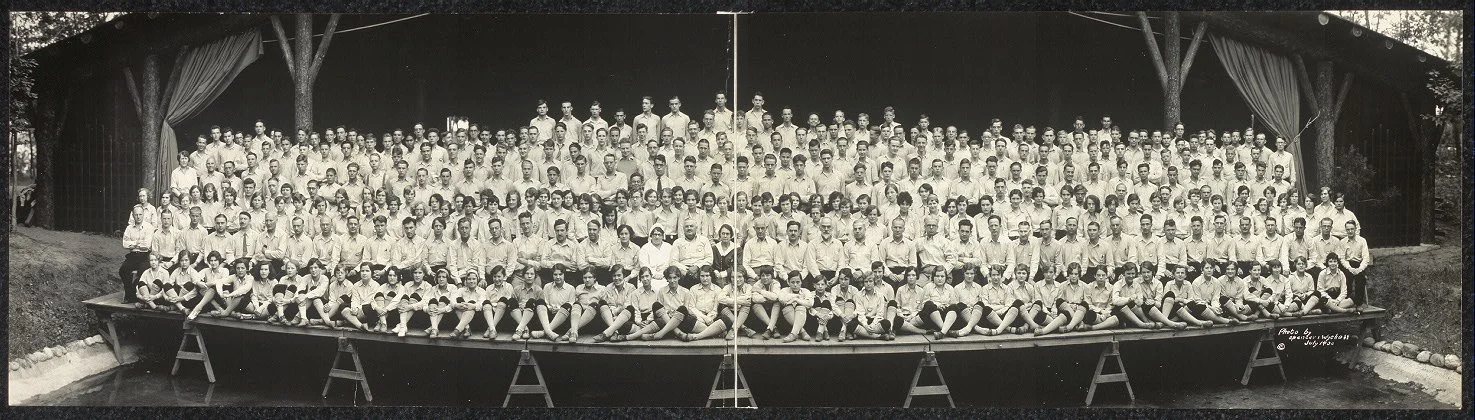

Personnel of National High School Orchestra, Interlochen, Mich., 1930; Photo by Spencer and Wyckoff; Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Harbor at Mackinac Island; Mackinac Island, Michigan, c. 1924; Courtesy of Chris Byron and Tom Wilson.

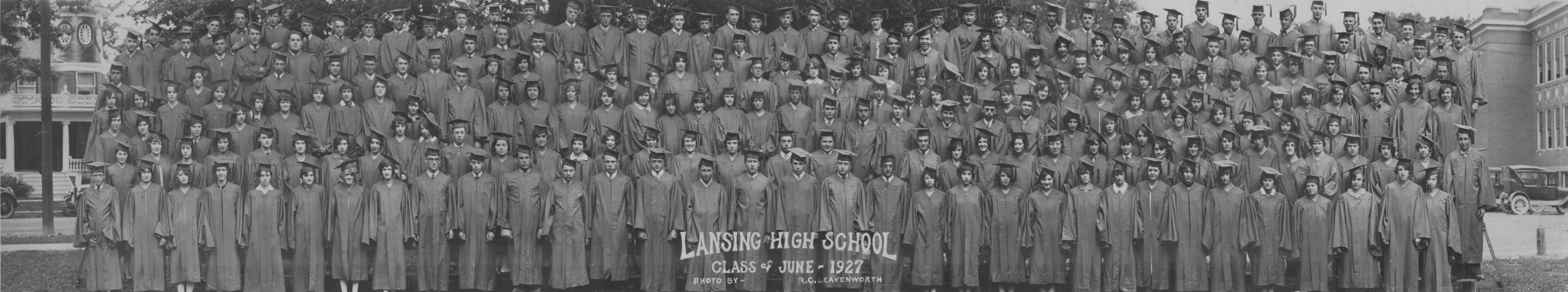

Lansing High School Class of June 1927; Photo by R.C. Leavenworth, Lansing, Mich.; Courtesy of the Dan Barber Collection.

Police on Motorcycles, unidentified; Courtesy of the Dan Barber Collection.

Camp Grayling; Photo by Mock, Big Rapids, Mich.; Courtesy of the Dan Barber Collection.

Truck and Tractor School, Michigan Agricultural College, 1921; Photo by R.C. Leavenworth per Harvey Photo Shop; Courtesy of the Michigan State University Museum.

West Intermediate School, Jackson, Michigan, 1922; Courtesy of the Dan Barber Collection.

A Great Lakes Cruise Ship on Lake Macatawa; Macatawa, Michigan, 1900; Photo by The Camera Shop, Grand Rapids, MI.; Courtesy of Lois Jesiek Kayes Collection, Historic Ottawa Beach Society.

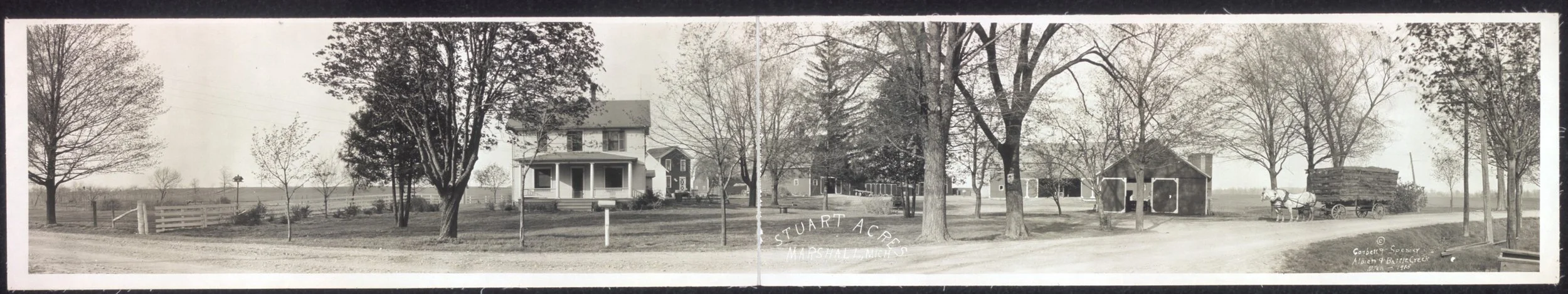

Stuart Acres; Marshall, Michigan, 1915; Photo by Corbett and Spencer; Courtesy of the Library of Congress.